This article by Prince Agwu was originally published by the Health Policy Research Group on 6 March 2020. The author is a researcher at the Health Policy Research Group (University of Nigeria), partner of the Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) Research Consortium.

Corruption is consensually defined as the use of entrusted power for private benefits. It tends to be prevalent within low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and most times attributed to poor governance and weak institutions. Nigeria as among the LMICs ranks highly in corruption indices in spite of the country’s anti-corruption agenda and institutions. The health sector is severely affected by corruption in Nigeria and stakeholders are increasingly getting uncomfortable with the situation, hoping that a change comes soon.

Most stakeholders lament corruption in the health sector, especially in areas of welfare and safety. A large number of recorded mortality cases and several negative health outcomes in Nigeria do bear a significant relationship with health sector corruption. In a recent article published in the International Journal of Health Policy Management by the Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) team on health in Nigeria, evidence of corruption in Nigeria’s health sector was extensively discussed. It was interesting to see health policy-makers and frontline health workers drawn from several geo-political zones in Nigeria passionately discuss a broad range of corrupt practices ongoing in the country’s health sector, as well as tenable solutions to them.

Notably, the participants agreed that corruption types such as absenteeism, bribery, procurement-related corrupt practices, health financing corruption, and employment irregularities are most common within the healthcare setting in Nigeria and should be urgently addressed. Unlike the everyday corruption-conversation that blames the government each time corruption is mentioned, the participants agreed that health workers, healthcare managers and service users, all have hands in the prevalence and sustenance of corruption in Nigeria’s health system. Therefore, they were critical of strategies to address health sector corruption to be a combination of vertical and horizontal efforts from the government and everyday people respectively. While vertical strategies emphasized the need to scale up welfare of health workers, governance, and stiff disciplinary measures, horizontal measures highlighted the need to increase alertness, ethical compliance and participation of the grass-root, civil societies and media in healthcare. Overall, there was the conviction that health sector corruption in Nigeria is addressable only if vertical and horizontal approaches will effectively align.

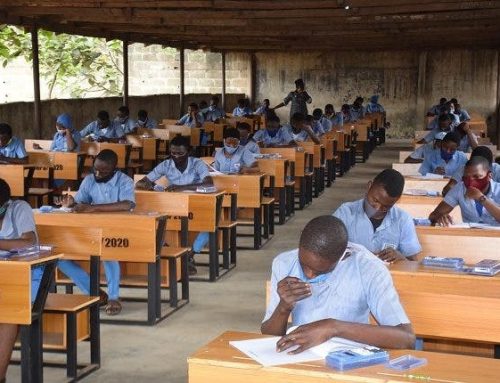

As a result of insights from participants, the team commenced incisive investigations into absenteeism of health workers in primary healthcare, knowing fully the importance of primary healthcare to the achievement of Universal Health Coverage. The team is also commencing the investigation of poor procurement practices in pharmaceutical departments of tertiary hospitals. On absenteeism, the ACE team is deploying both qualitative and quantitative approaches, through utilizing interviews, focus groups, questionnaires and the discrete choice experiment (DCE). While the qualitative approaches offer extensive description and deeper understanding surrounding the dynamics of absenteeism of health workers, the quantitative approaches help to prioritize interventions.

For instance, a pilot survey done by the team with 30 primary healthcare staff reveals that sampled health workers are of the opinion that they would intensify commitment to their jobs if job satisfaction is improved in terms of transportation allowances and avenues where they could express their dissatisfying concerns. They were less bothered about living quarters, further educational training, or stiff disciplinary measures. Findings from the quantitative aspect of the study seem interesting at the embryo stage. Nevertheless, the main study is about commencing with a larger number of respondents. In the end, a synthesis of the qualitative and quantitative findings will be achieved, which will help for an effective design of policies and programmes that can effectively combat health sector absenteeism in Nigeria. Same process will be adopted to understanding and tackling corruption in the pharmaceutical sector of tertiary hospitals in Nigeria.

Photo credit: ACE team of the Health Policy Research Group (HRPG), University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus